26/02/2020

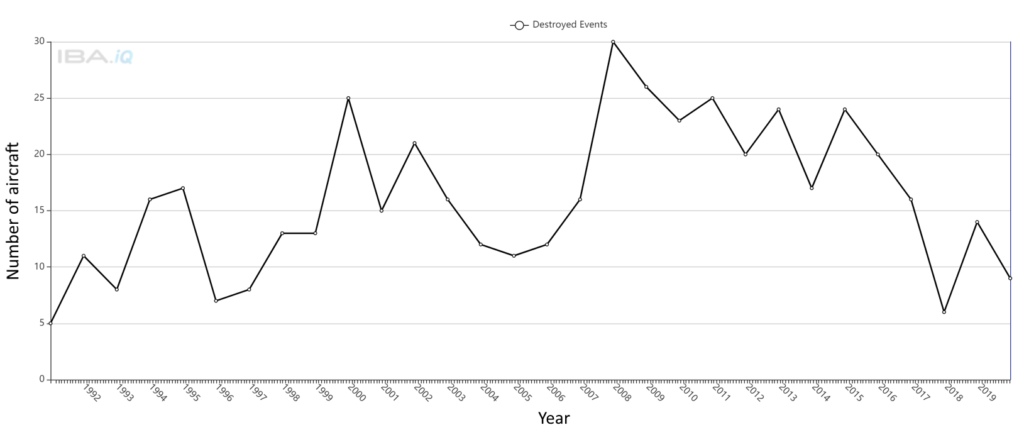

Two fundamental situations have prompted IBA Group and Split Rock Aviation to reflect on some key 'industry standard' provisions within aviation lease agreements and re-evaluate their applicability and relevance: the 737 Max's grounding and the continued growth of leased aircraft in the industry. With the proportion of commercial aircraft leased now at 44% compared with 56% owned according to IBA's intelligence platform IBA.iQ, and witnessing the aviation industry's handling of the 737 Max's grounding, we have produced the first in a series of articles considering today's operating lease agreement. This segment will assess several industry standard lease agreement positions and test their logic in the current market.

Many standard lessor positions have been established over the last several decades using the logic: "If you, the lessee, owned this plane you would incur this cost or responsibility." As a high-level introductory question, can you think of any other industry as successful as our own in blurring the relationship lines between the benefits and burdens of ownership versus the cost and flexibility of leasing an asset? It is through this lens that we have considered the benefits and responsibilities of ownership compared with leasing.

The hell or high water clause is the foundation stone of aircraft operating lease agreements and it, or its equivalent, form part of every lease we review at IBA. Simplistically, this clause is the absolute contractual obligation every lessor and lessor investor relies upon. It requires that, come what may, the lessee must meet all its obligations first and then use appropriate systems to settle any disagreement, be it arbitration or through the court system. Let's take this clause and pretend for a moment that it's now within the fine print of a car rental agreement. If the car was suddenly deemed unsafe and forbidden to be operated, would you think it normal and reasonable for the hirer to still pay the rental, or the insurance, or be responsible for the vehicle's required maintenance and storage costs whilst it is laid up and cannot be used? More succinctly, would you expect the full cost burden, including loss of operation, to be the hirer's responsibility?

Viewing the hell or high water clause from this perspective, it is a challenge to hook onto a logic strand supporting the argument that an airline must continue to pay its lease rental for an aircraft that cannot fly. When an aircraft loses its certification, what precisely is a lessee still paying for? How did we reach a position where a lessee is contractually obliged to pay the lease rental on a nonperforming asset? The hell or high water clause was originally intended to cover operational or commercial disagreements between lessor and lessee, not the asset's grounding. With the Max's withdrawal, many lessors recognised this and were quick to step up and provide relief. A small number have, however, used the hell or high water clause as a shield which, you could argue, is detrimental to a business built on long-term relationships.

The grounding of an aircraft is significantly more impactful on airlines than on established lessors. Let's apply the first test of the benefits of ownership versus leasing: if the lessee owned the aircraft they would have this exposure. But they did not buy the aircraft, they rented it from you, the lessor. They pay more monthly for the benefit of renting or leasing than would typically be the case for a straightforward financial instrument to buy the plane so why should the lessee now assume the costs or responsibilities of ownership? If, as an airline, I bear the cost of your ownership as lessor, would it not then also be reasonable for you as lessor to share the burden of my operational risk? Why should the lessee also have to cover the cost of insuring, storing and paying the calendar-generated aircraft maintenance reserves? If the lessor's asset never flies again, am I as airline responsible for paying for the rest of the lease term too?

Looking ahead, it seems logical to support the position that the Max's grounding will drive changes to the hell or high water clause, it being likely that an aircraft's grounding will be carved-out, which in turn should trigger a lease rental freeze. In addition, other associated costs could be on the table for discussion, specifically insurance and maintenance costs. This also raises the question of whether lessees should have an obligation to extend leases to make up for the grounding period, the most popular lessor fix to date, or if the burden of a nonperforming asset should remain with the owner, not the party renting it? The concept of the lessee being bound to make the lessor whole, while at the same time suffering costs and damages of its own, seems a challenging one for those unfamiliar with our industry. Its inequity means we expect to see some carve-outs to protect lessees in the future.

In the event of a Total Loss

If we accept the logic used to argue amendments to the hell or high water clause are necessary, this clause gets more interesting. Let's take hull insurance practices in our industry and consider them through the lens of ownership benefit or burden. Routinely, an aircraft's hull value is insured at a premium to the book value. The standard practice is to insure an aircraft for 105 - 120% of the lessor's book value, the range depending primarily on the lessee's standing. Lessors offer two reasons for this centering on:

It being a requirement driven by a financing covenant or

In the event of a total loss, payment of the insurance settlement can be protracted and the loan must still be serviced and other costs paid in the interim.

Many legacy lessors are now investment grade and raise corporate unsecured debt; the financing covenant from days gone by no longer exists. Even if the covenant does feature in a lessor's financing facility, such as an ABS or transaction-specific debt, should an airline pay for covenants or conditions that the lessor itself has signed up to when financing the aircraft?

Secondly, all leases stipulate that in the event of a total loss, lease payments must continue until insurance proceeds are received. This leaves us in the position that, on the one hand, the hull's value must be insured at a premium because the lessor still has expenses to pay and, on the other hand, the airline must continue to pay its lease rental because the lessor still has expenses to pay. Logically, only one of these positions should be relied on at any one time. If you were the airline, would it not be reasonable to want to either insure the hull at no premium or remove the requirement that I pay both the premium and the lease rental?

In most lease negotiations, there is a tussle over what happens to the maintenance reserve pot in the event of a total loss of the aircraft. Lessees tend to argue that it is a cash grab by lessors; lessors respond by claiming the maintenance reserves were paid to cover utilisation costs incurred against the aircraft and, the total loss notwithstanding, this aspect remains unchanged. One thing is certain though: a lessor will not use the ownership argument in this instance because if the lessee were the aircraft's owner, they would keep the maintenance reserves. Whilst splitting the maintenance reserve pot 50:50 between lessor and lessee is a reasonably common negotiated outcome, there is still ample room to reflect on whether a fair result has actually been achieved. Such an outcome can still create the impression that the lessor is profiteering. This perception is created in four ways:

Lessors state maintenance reserves are not a profit center but, if there is no longer any maintenance to be performed, the lessor is taking the maintenance reserves to profit. While that is also true of the airline if it acquires the maintenance reserves, these funds start life as an airline expense

You could argue the unexpected removal of an aircraft from a lessor's business plan leaves a revenue hole. Try that logic out on the airline that's an aircraft down in its operation and is thus facing significant disruption and cost

The lessor already requires the aircraft to be insured for a value higher than its book value and the difference between the aircraft's insurance and book values represents profit for the lessor

If the first three rationales don't grab you, try this one: lessees pay for aircraft utilisation via either maintenance reserves or, for better established credits, through return compensation payable at the end of a lease. All other aspects of the calculation being equal, in the event of a total loss the lessor does not ask an airline for return compensation to pay for utilisation incurred to date against an aircraft that no longer exists. It would be a tough ask, which is why lessors don't do it. How then can a lessor justify retaining maintenance reserves in scenarios not involving a total loss and defend their action as reasonable or justified?

IBA considers the total maintenance obligations of leased aircraft to be close to 25bnUSD per annum. Approximately 50% of that 'spend' will be paid to lessors in advance via cash reserves and/or letters of credit arrangement. Some airlines prefer to mange their cashflow in this way but, in the event of loss, paying for future maintenance which is no longer required seems unfair. Lessors are keen to hold the cash for these events: it provides a huge advantage and, in many cases, supplements their overall IRR. This has been especially important when lease rentals have been reducing in real terms.

AD Cost Sharing has long been a battleground point in lease negotiations. Over the years, lessors have conceded one small step at a time in the form of USD contribution thresholds, the time period over which the AD cost is amortised and the timing of the lessor AD contribution. As can be the case with industry norms and standards, participants may become accustomed to playing within a defined parameter without stepping back to re-evaluate how well the established boundaries fit.

Here again lessors typically approach the subject using the logic that "if you, the lessee, owned the aircraft, you would incur this responsibility anyway". A fresh look at this issue suggests it can be split into two components:

ADs are issued to correct perceived design deficiencies of some sort

ADs are issued and other mandatory compliance is required that specifically relate to the aircraft's area of operation

In the case of design-related ADs, an airline could adopt the position that yes, if I owned the aircraft I would be required to comply. But, luckily, I lease the aircraft from you, the lessor, so shouldn't you as owner be responsible for the cost of remedying a deficiency that I did not create in your own asset? I would expect that to be the case if I rented a car or a house, for example. Developing the argument, the ramifications are more complex than just the cost of AD compliance. What if the AD triggers additional inspections that would otherwise have been unnecessary and there are now new findings to remedy? On whose account should this be? There are numerous benefits for owners and, whilst it may seem attractive to move the burdens of ownership to another party, correcting aircraft deficiencies is a responsibility that aligns more reasonably and naturally with the owner.

The flip side of this scenario is also true. If an airline is required to perform mandatory modifications to an aircraft because of the jurisdiction within which it operates, there is little value or case for the lessor to cost share unless the follow-on lessee is in the same jurisdiction. Then, an airline could argue the lessor will benefit from the investment it made and provisions for cost sharing can readily be captured in the lease agreement's drafting. The concept established, precise details of the cost sharing would occur closer to the end of the current lease term.

We have seen some differences in definitions across various lease agreements. Some specifically limit the sharing to the AD only but others cover broader mandatory operational matters. This first came to light in the late 1990s when TCAS (Traffic alert and Collision Avoidance Systems) were mandated in the US and other regions took a few years to follow suit. Similarly, post 9/11 reinforced cockpit doors became a requirement, not due to any specific design deficiency but based on common sense security opinion. "Who should pay?" was a common question.

The aviation operating leasing industry is mature, accepted and growing. As it has evolved though, we believe it's time to consider whether lease agreements have developed along with it and if it makes sense to reassess certain sections of a lease that we currently accept as industry standard. We propose this debate not from the viewpoint of introducing new negotiation topics and areas of contention, but from a position of logic: can a lease's clause pass the simple test of, when read aloud, making sense and sounding fair?

- Andy Mansell, Partner Split Rock Aviation

- Phil Seymour, CEO IBA Group

Andy Mansell has over 25 years' operating lease experience and is the co-founder and partner of Split Rock Aviation, an aviation advisory firm.

About Split Rock Aviation

Split Rock Aviation is a finance and lease advisory firm whose partners are made up of a team of senior executives with over 100 years' collective experience. We specialise in finding innovative solutions for everything from single asset transactions to enterprise level strategies. The team has worked together extensively and learned how to apply each partner's unique skills to meet clients' needs.

筆者

プロファイル全文を表示関連コンテンツ