15/06/2021

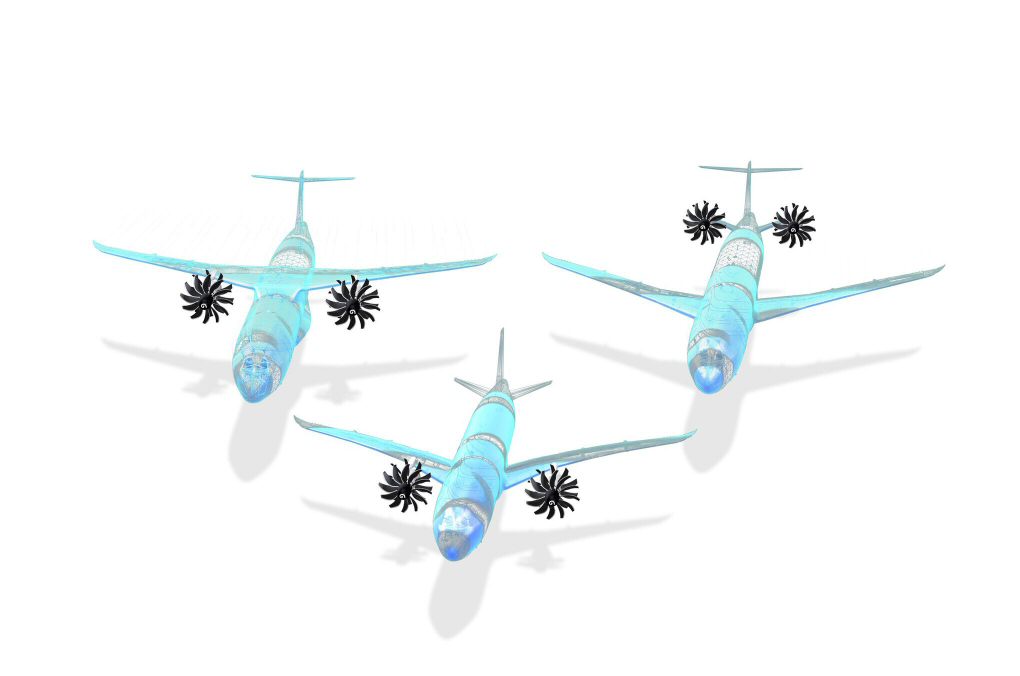

General Electric and Safran Group are to collaborate on the development of a viable open-rotor engine, 'RISE', destined to power narrowbody aircraft by the mid-2030s. The joint venture between the US and French aero engine giants, named CFM International, intends to make workable a concept first touted in the 1970s. The open-rotor engine dispenses with the traditional pod housing the fan blades seen on high bypass turbofan engines.

Since the first concept of using swept wings to reduce aircraft drag was introduced in the 1940s, research into the viability of fuel-efficient propulsion systems for commercial aircraft has taken many different iterations. The original development of open-rotor engines, also known as 'propfans' and 'unducted fans' saw this technology expanded significantly during the 1990s and early 2000s, with several prototype designs and test flights conducted by major manufacturers. However, these never truly gained traction due to several key disadvantages. These ranged from issues with excessive noise to business and economic constraints at the time.

In a new era of environmental limitations and pandemics, could the targets aviation has set itself for the next decade prove the perfect breeding ground for the open-rotor?

There have been significant advancements in gas turbine technology over the last decade in a bid to reduce engine fuel consumption, most notably the Pratt & Whitney Geared Turbo Fan, Trent XWB and CFM LEAP engines. Aircraft fleet data from IBA Insight currently shows 1,090 active aircraft globally powered by CFM LEAP family engines, all of which are Boeing, Airbus or COMAC types. The open-rotor concept is intended to be a successor to the CFM LEAP 1 turbofan engine, especially as the constant requirement to reduce emissions further has driven investment into developing more disruptive technologies within this aircraft class.

Source: CFM

An open-rotor engine functions through a pair of large, counter-rotating propellers that generate thrust without the encasement typical of traditional turbofan engines. It begins by drawing in and compressing air, which subsequently passes through the open rotor. Here, the rapid propeller rotation accelerates the air, leading to thrust generation. A critical factor in the success of open-rotor engines is the bypass ratio, denoting the amount of air diverted around the engine core compared to the portion that flows through it.

Contemporary turbofans typically feature a bypass ratio of 11:1, signifying 11 units of air bypassing the core for every 1 unit passing through it. In contrast, the CFM RISE program anticipates a substantial bypass ratio of 75:1, which holds great promise for improved efficiency. However, the introduction of a larger and more potent engine presents weight considerations, necessitating adjustments such as higher landing gear or wing configurations to accommodate the increased weight and size.

The design of an open-rotor engine aims to reduce fuel consumption by 20% compared to traditional turbofans and to reduce noise when compared to conventional gas turbine engines. The CFM RISE project tests key aspects in the design that included aero-acoustic optimisation, pitch control systems, contra-rotating reduction gearbox, lubrication, and cooling systems as well as the rotating parts within the nacelle.

Notably, noise issues were one of the key barriers to the success of the original open-rotor development. The finished product would also be compatible with Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAF), as well as potential hydrogen fuel capability. IBA believes the open-rotor has the huge potential to disrupt and change the engine market - though it should be noted that with delivery not expected until the middle of the next decade, timelines may prove problematic for some OEMs.

_McDonnell_Douglas_demonstrator,_Farnborough_UK_-_England,_September_1988_(5589809360).jpg)

Source: Andrew Thomas

Environmental, Social, and Governance issues are now seen as a key risk to investments which is why authorities across the world are demanding more transparency and stricter reporting standards in all sectors including aviation. IBA employs ESG experts who truly understand the aviation industry. We can help ensure reporting is compliant with new regulations and best practice. Our team support in forecasting the future cost of carbon offsetting (which can run into the billions of dollars for a single airline) and advise on operational improvements to mitigate some of these costs.

Related content