10/07/2023

Claims surrounding the concentrated socioeconomic nature of air passenger demand are widespread. In North America in 2017/18, 19% of the population took 4 or more flights per year; accounting for a staggering 82% of all flights in the region[1]. The argument put forwards by those advocating for a frequent flyer levy (FFL) is that the small proportion of populations that fly regularly should be paying for the disproportionate impact they have on aviation’s emissions.

While accurate data containing both how often an individual flies per year and their location, income, profession, etc., isn’t readily available, we can utilise publicly available data on passengers and prior research to draw insights on global and UK passenger demand.

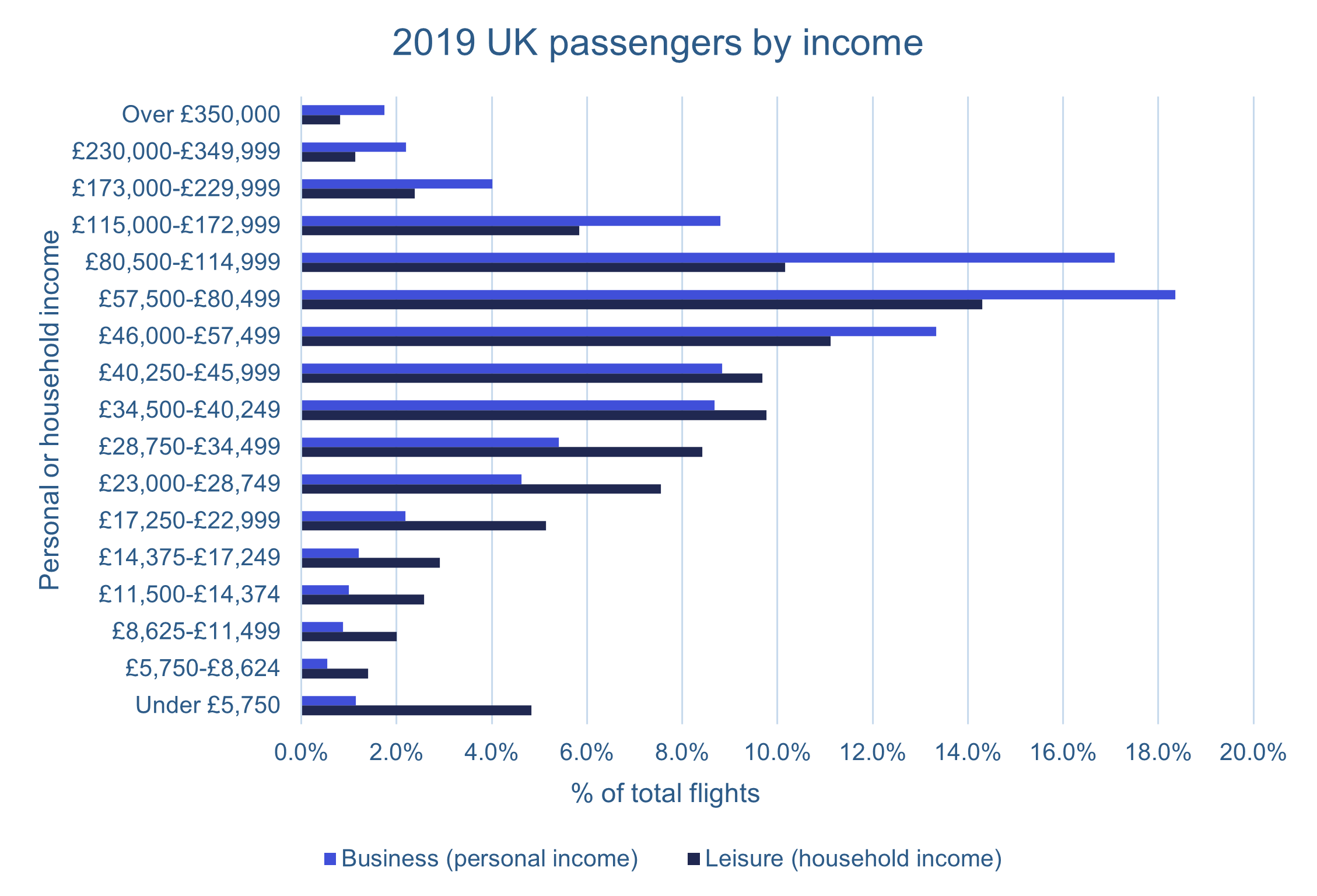

Figure 1 - % of total flights by passenger income (Source - CAA)

The CAA’s departing passenger survey[2] from 2019 sheds light on the passenger income levels that most frequently passed through the UK’s airports: representing around 240 million terminal passengers. 65% of all leisure seats were taken by individuals coming from households with income above £34,500, with the most common household income being between £57,500 and £80,499. With business passengers, the prevalence for high income is even more pronounced, especially when considering that their responses refer to personal income. 83% of business passengers earned over £34,500, and 58% earned between £46,000 and £172,999. While it’s unsurprising that the income profile of business passengers is skewed further towards the higher end, the mode of respondents’ income across both business and leisure trips is between £57,500-£80,499.

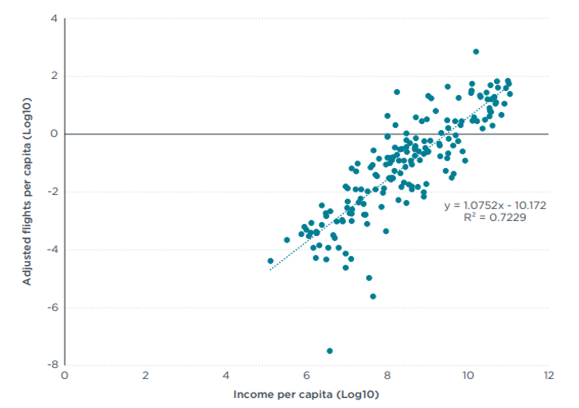

Despite the CAA’s publicly available data providing a snapshot of passenger income and in theory, how able they would be to pay an additional FFL, it doesn’t provide any data into how many additional flights these respondents take in a year. The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), who released one of the most in-depth studies into a FFL in 2022, collated data on income per capita and flights per capita into a log-log regression. The relationship between income and flights, as shown in Figure 2, is statistically significant (p<0.05). The study is global and as such is weighted towards countries with higher income and/or larger numbers of visiting tourists.

Figure 2 - log-log regression of global income and flights per capita (Source - ICCT)

The argument for a FFL is justified on both a global and national scale, and the UK saw the largest adjustment increase of total passenger numbers of any country, weighted by aviation traffic and per capita income. Although the implementation of a global FFL would require unprecedented levels of unilateral cooperation, this study provides explanation for why talk of demand managing policy in aviation is getting louder in the UK.

However justified a FFL would appear to be, operators will continue to be guided by regulators on best-practice in creating net zero pathways and currently, few major institutional bodies recognise demand management as a key component of meeting net zero.

|

Institutional body |

Recognises demand management? |

Context |

|

ICAO [3] |

✖ |

ICAO do not recognise the role of demand management in meeting net-zero by 2050. They place heavy emphasis on the success of CORSIA in providing a credible offsetting scheme and a robust network with which to develop SAF supply and distribution, alongside aerodynamic and hydrogen technology. |

|

IATA [4] |

✖ |

IATA cite four pillars to meeting their net-zero goal by 2050: 65% SAF, 19% offsets and carbon capture, 13% new technology, and 3% operational efficiencies. IATA’s position is that decoupling emissions from travel growth should come solely from these four pillars. |

|

✔ |

The EU states that to successfully reduce emissions there must be measures additional to typical pathways, including fiscal and behavioural measures addressing demand. Demand management not explicitly included in roadmap, but demand reduction is shown as an effect of SAF and economic measures. |

|

|

Sustainable Aviation UK [6] |

✔ |

Sustainable aviation’s net-zero pathway incorporates typical components of SAF, market-based measures, and efficiencies, but includes the effect of a carbon price on demand, which increases as the carbon price ramps up towards 2050. It’s included as a benefit of a high carbon price, rather than a component of decarbonisation. |

|

Climate Change Committee (CCC) [7] |

✔ |

The CCC, who set the UK’s carbon budgets, include demand management in their balanced net-zero pathway, particularly between now and 2030. They state it plays a critical role in ensuring emissions continue to decrease while SAF and efficiency benefits begin to scale up, and there should at no point be a net expansion of UK airport capacity. |

|

UK Department for Transport (DfT) [8] |

✖ |

The UK government promotes the ETS and CORSIA as key measures in their Jet Zero strategy, alongside efficiency, zero-emission flight, SAF, and abatement out of sector. On demand management, the government has previously asked for consultation, but is clear that they don’t believe demand management is necessary and instead see recent adjustments to APD as sufficient, despite the recommendation of the CCC. |

Table 1 - Key institutional attitudes to regulation (adapted from Possible (2021)

Unsurprisingly, given the concentrated nature of global flights by wealthier countries shown in Figure 2, both of aviation’s major international bodies do not advocate for demand management. What is surprising is that despite recommendations of the CCC, the independent body that advises the UK government, Jet Zero strategy remains opposed to implementing demand management. Instead, the UK will adjust its primary form of aviation taxation, air passenger duty (APD), in 2023 to place higher rates on long-haul sectors and reduce those on domestic and short-haul: an adjustment that was designed to have a negligible impact on emissions[9].

Despite the ICCT’s proposal of a global FFL, both the attitudes of unilateral institutions and the make-up of aviation demand point towards a more targeted approach if demand management is implemented, at least in the near term. IBA’s view is that aviation finance stakeholders and operators should be aware of the potential impact of a FFL, as pressure on the UK government to remain on target to meet Jet Zero is likely to increase as we approach the first 5-year strategy review in 2027.

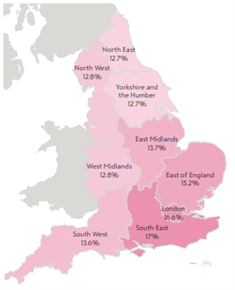

Figure 3 - Regional demand reduction in 2050 compared to no policy change (Source - New Economics Foundation)

A key component of a FFL is that it would not impact England in an equal manner, as figure 3[10] shows. As opposed to the government’s APD amendments, a FFL would target the regions most responsible for aviation emissions: London, the East and the South East. The top income group could see a demand drop of up to 30%, a group that is concentrated in the South East. The impact on the UK’s aviation industry would be regionally diverse.

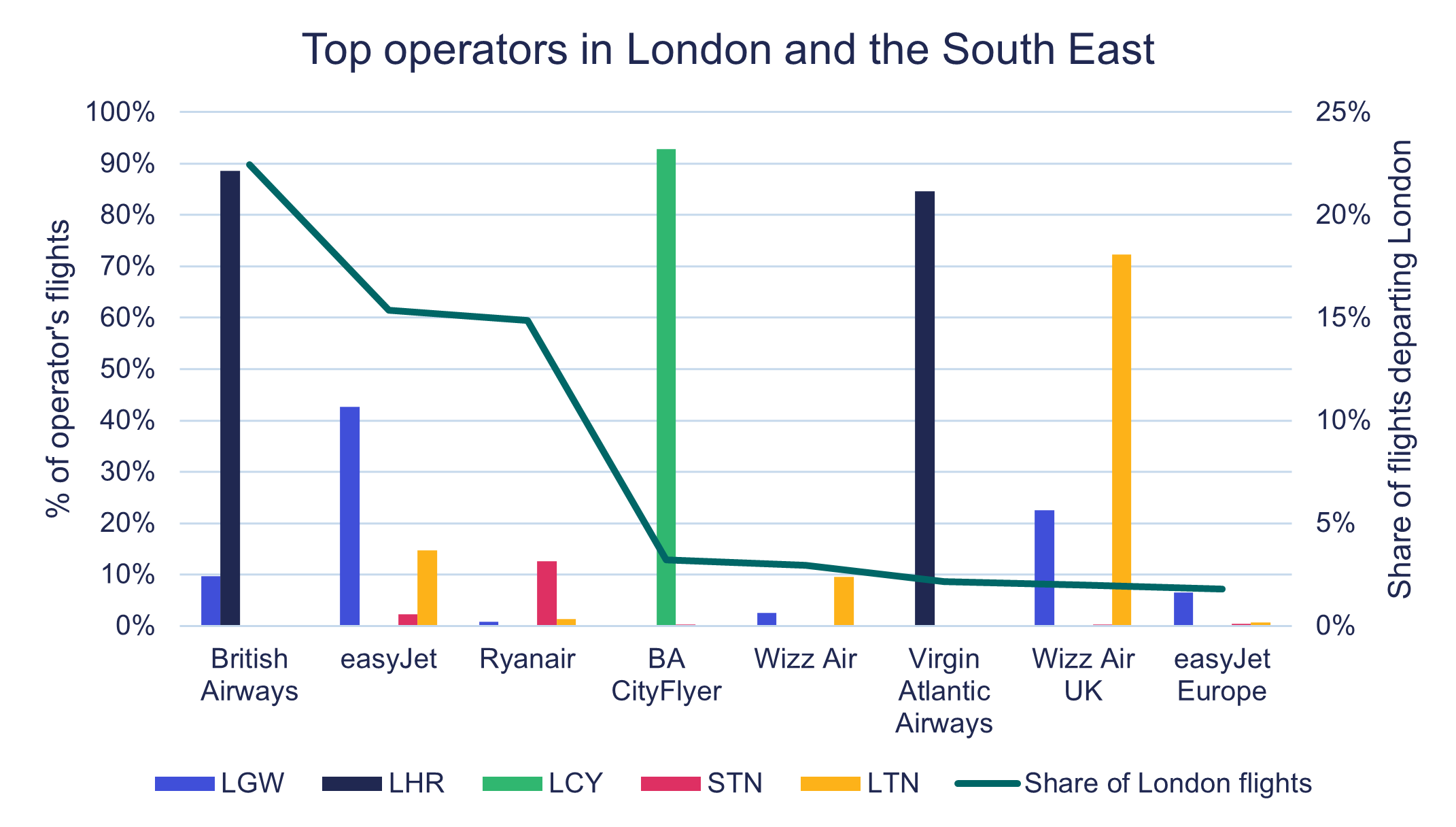

While it’s difficult to accurately determine the impact of a FFL on demand or revenue, we can study existing networks. Figure 4 displays the top 8 operators most exposed to a FFL, if demand management was introduced and passengers reacted to higher price signals in London and the South East. These operators account for 65% of flights out of London. British Airways hold the largest share of all flights departing out of London airports, at 22%, while also only operating out of either LGW, LHR, or LCY: the most expensive for operators and passengers. In contrast, operators such as Jet2 and TUI would be less affected, with hubs in the North and East Midlands. Low-cost carriers easyJet, Ryanair, and Wizz have a more diverse operating structure and fly out of cheaper airports within the London area. In response to a progressive tax, passengers would seek the cheapest tickets to offset the cost of each additional flight, while operators would begin to see increased competition.

Figure 4 - Top London operators and their exposure to a potential frequent flyer levy (Source - IBA Insight)

In the immediate future, a FFL is unlikely to be implemented in the UK. The government sought consultancy on stakeholder views towards demand management in 2021 but found opposition in the form of data privacy issues and increased administration, as well as the obvious impact of lowering demand, which won’t be felt equally across operators. Despite this, the UK plans to have five SAF plants under construction, a SAF mandate, and changes to airspace operations, all by 2025[11]. This will require considerable funding and operators have made it clear that a jet fuel tax is unfavourable, due to concerns around keeping revenues in sector. On the demand side, the fairest option is to tax those most responsible. Pathways to decarbonise aviation will need to explore all options, especially as economic headwinds continue to occupy the industry. It is vitally important that all stakeholders remain engaged and cooperative in what is a crucial period of aviation’s transition.

[1] Possible (2021) Elite Status - global inequalities in flying

[2] CAA (2019) Departing passenger survey 2019 reports

[3] ICAO (2022) LTAG Special Supplement

[4] IATA (2021) Fly Net Zero

[5] Destination 2050 (2022) A route to net zero European aviation

[6] Sustainable Aviation (2023) Carbon Roadmap

[7] CCC (2022) Progress snapshot

[8] DfT (2022) Jet Zero Consultation

[9] UK GOV (2022) Air passenger duty band reforms

[10] New Economics Foundation (2021) Frequent Flyer Levy

[11] UK GOV (2022) Jet Zero Strategy