When we think of capacity growth since 2020, we largely visualise the slow return to service of the fleet. It’s still true that the stored fleet continues to remain a problem for some types. And it’s generally up across the board either because there is insufficient demand, labour, or hours and cycles remaining to support a return to service. Of course, it’s not as simple as that and we are all well aware that the in-service fleet is not being utilised in the same way it was back in 2019. Certainly, widebodies have been re-purposed and there has been a greater inwards focus regarding regional travel that remains sticky. How this affects overall capacity is quite significant as you could largely have the same number of overall passengers and trips as before, but flying totally different legs as the reasons for travel and costs continue to evolve.

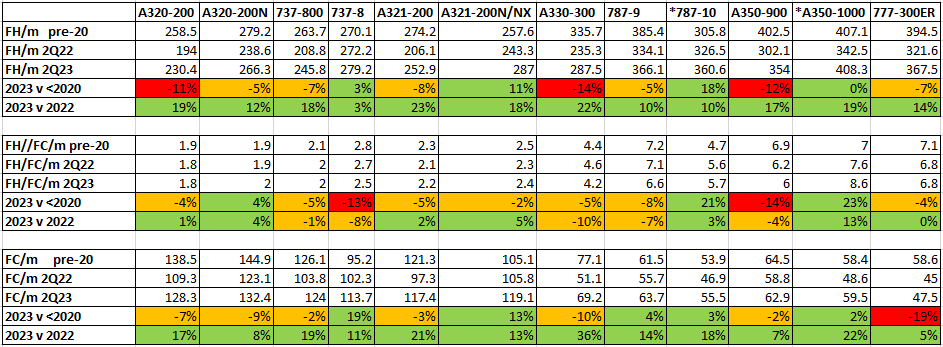

I have tabulated the average monthly hours, sector lengths and cycles for 12 of the most popular passenger aircraft in operation and highlighted the variance to previous periods.

Looking at the data, for the most part, compared to the same period last year, total utilisation for the largest portion of the fleet continues to grow. In all cases for the types in question, average monthly hours and cycles have grown since last year. However, that does mask the fact that in some cases, the average sector length has reduced. This is, however, generally reflected in the larger rise in average cycles to account for it.

The largest disparities continue to remain when looking back over a longer period, whereby only the latest technology aircraft have shown signs of growth. As expected, the more capable and more economical replacements have performed the best but it’s not necessarily even across the board. On the narrowbody front, whilst the monthly average cycles have increased by 19% for the MAX 8 compared to the period before the grounding, the A320neo continues to lag somewhat, due to global distribution variances and an unsynchronised recovery. For the widebodies, it’s the larger new technology variants that have shone through.

Whilst I would expect the utilisation of ageing aircraft to reduce over time, lags of this size indicate that the system has some way to go before optimum use has been achieved if I’m to assume that the way in which aircraft are used hasn’t fundamentally changed. Certainly, from my own experience, airlines will still readily cancel flights at short notice if demand is slow to respond (although they may use a technical or lack of staff excuse). Looking forward, it’s encouraging that growth rates are positive still, but we can’t ignore the fact that demand remains sensitive in the current economic environment on a systemwide basis. For the time being at least, utilisation continues to grow at a largely consistent rate but that still indicates yet another year of recovery. Even when looking at the industry workhorses, the A320-200 and 737-800, even with a 10% smaller fleet, utilisation remains down 11% and 7% respectively.

Source: IBA Insight & Intelligence

A frequent conversation has been whether the consumer’s pent-up demand would endure until Q3. The busiest season and continued high fares would then give the industry a chance of more record revenues. This appears to be the case with Delta and United’s profits coming out this week.

Delta’s $15.6bn quarterly revenue and $2.5bn operating profit (margin 16.0%), was their highest ever, in a Q2! Full-service carriers have benefitted from getting their long-haul networks back online, and Delta has cited their joint ventures with Korean Air and LATAM as bolstering that trend. Favourable scheduling between airlines reduces direct competition on routes whilst also providing more variety in timings for the consumer. Delta have also signed a similar joint venture with El Al this year; this is in addition to being part of the Sky Team Alliance.

United’s $14.2bn quarterly revenue was also a record for them, achieving an operating margin of 10.7%. The airline credits extra revenue to a 32% expanded transatlantic network (vs 2019). Both airlines also recorded H1 operating profits (5.6% margin for United and 7.8% for Delta).

In terms of profitability, as expected, fuel price has been a large driver. Despite an increase in ASKs in H1 of 18% for Delta and 20% for United, the fuel cost was largely flat for both. This is reflective of crude oil (WTI) sitting at $76 a barrel, down from highs of $117 in June 2022. United and Delta each increasing their load factors by roughly 3 percentage points to 83.4% and 84.8% respectively also helped. These are high for full-service carriers.

IBA has previously pointed out that one of the reasons that capacity has not yet recovered to 2019 levels may not be demand related. Airlines may be restricting capacity to keep these load factors high, with margins alongside them.

Going forward, OPEC are likely to protect the fuel price from falling further, even if Russia were to reconcile with The West. A cost that is still of concern is staff, however. American Airlines staff have set a date for a strike vote, whilst United have had to recently agree on another new staff contract. Across the pond, easyJet also blames their recent 1700 cancelled flights on staff shortages in aviation infrastructure like ATC, as well as potential strikes. All the pieces are in place for record Q3 results, it is a question of how much strikes can dent them.

Last year, Wizz Air exercised its options to purchase another 75 Airbus A321neos and it would appear it started a global trend towards larger narrowbodies. Although the A320 family split of the Indian Paris Air Show orders is to be confirmed, there has been a recent preference for the A321. This includes Viva Aerobus (90 aircraft), Icelandair (13 aircraft and 12 options) and finally Pegasus upping its A321 order by 36 this week.

These recent orders have resulted in the Airbus A321neo overtaking the A320neo in net orders, making it the most-ordered Airbus aircraft. The A321’s max capacity of 240 seats offers a clear advantage over its 180-seat smaller counterpart and finds itself very popular among growing demand, specifically on the high-density routes between airports with infrastructure constraints. The up-gauging trend was not exclusive to Airbus. In May, Ryanair announced a massive order of 300 737 MAX 10s (150 firm and 150 options) – Boeing’s biggest narrowbody variant. This would suggest that airlines’ effort to up-gauge the capacity amidst growing passenger demand and increasing delivery times is well underway.

Moreover, with airlines’ effort to pursue net zero targets becoming more apparent, the A321neo offers yet another advantage with its average CO2 emissions per-seat per-mile being lower by 3% according to IBA NetZero.

It would also appear a similar trend seems to be happening in the widebody market. This week Emirates modified 16 777-8s to 777-9s in their order backlog. This now means that their entire 777 backlog is for the larger variant (115 aircraft). Airlines, such as Emirates are starting to look for the alternative for their ageing fleets of A380 superjumbos. However, with Airbus currently not offering anything beyond significantly smaller A350s and the 777X-8 being delayed in favour of the freighter variant, carriers are limited in terms of large widebodies available. For now, the answer appears to be the upcoming Boeing 777X-9 with its 426 seats. This could become the new Gulf flagship aircraft.

Our weekly update looks at the key trends and market indicators using data and analytics provided by IBA Insight.